Dai Sil Kim-Gibson: An Appreciation of a Career

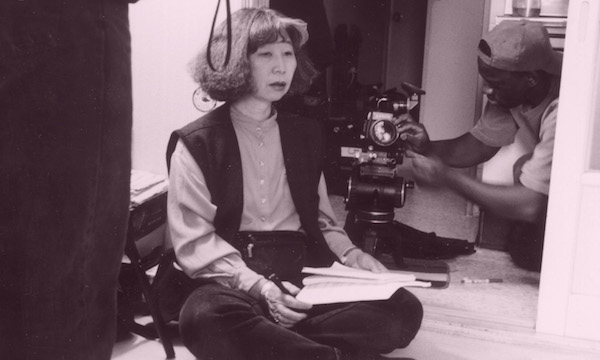

/PHOTO: COURTESY THE DIRECTOR

FESTIVAL SPOTLIGHT ARTIST By Abraham Ferrer

To generations of Asian Pacific American cinema artists and arts policymakers, Dai Sil Kim-Gibson has been many things — maverick filmmaker, staunch arts advocate, devoted spouse and closet renaissance woman. While I have not known her as long or as intimately as her contemporaries, she has certainly been impactful to me in the years that I have been involved with organizing this very Film Festival.

For one thing, Dai Sil has been That Filmmaker Whose Screening You Don’t Want to Screw Up, Or Else: the first time we screened her magnum opus on Korean sexual slavery, SILENCE BROKEN: KOREAN COMFORT WOMEN, back in 1999, we learned too late that her 35mm film print was mixed in Dolby SR, which could not be read back clearly by the theater’s sound system. As a result, all the subtlety of Jon Oh’s sound design was lost, reducing her Los Angeles premiere to a screening that might as well been in mono. That cringe-worthy experience paled in comparison to my first face-to-face meeting with Dai Sil, whom I had previously met through a series of phone calls in the weeks preceding Festival Week. Approaching her in the lobby while her film was screening for what turned out to be an otherwise oblivious audience, I offered a weak apology for the audio issues that turned up. To this day, I don’t really remember her actual comments which were icy enough, but I could never forget the withering glare she fixed on me through her wire-framed glasses as she expressed a series of “these things happen” laments — as if she was telling me through those “look-daggers”: You Eff’d Up. Royally. Afterwards, as she conducted an impassioned Q&A session with the audience, I made myself scarce, so embarrassed was I at screwing things up so badly. Apparently, I still had much — so much — to learn about correctly presenting a filmmaker’s work.

Dai Sil has also been That Artist Who Offered Second Chances: four years later, I had the fortune of organizing another Los Angeles premiere for her, this time a screening of WET SAND, an even-handed, nuanced assessment of Los Angeles ten years after the Rodney King beating verdicts and the 1992 L.A. Rebellion that quickly followed it. The stakes were arguably higher this time, as her latest film sought to contrast the differing community-rebuilding trajectories of African American and Korean American communities after The Rebellion. The large audience that turned out was understandably apprehensive about how an elderly Korean American woman — an outsider from New York City, at that — would portray their lingering issues of perceived animosities toward one another. This time, the screening was received much more positively, and, through working largely by phone from opposite sides of the continent, Dai Sil and I were able to actually pull the screening off (admittedly, with the help of the Visual Communications staff and the large network of Korean and African American churches and community organizations that she tapped to host a pre-reception and develop her premiere audience). One big takeaway: the lingering mantra by African American tastemakers in reaction to the premiere: “Her story treated us fairly.” The other takeaway: that Dai Sil and I were speaking and working together again. To this day, that was and remains a huge relief to me.

DIRECTOR DAI SIL KIM-GIBSON IN CUBA, CIRCA 2006 TO SHOOT HER DOCUMENTARY "MOTHERLAND." (PHOTO: COURTESY THE FILMMAKER)

Of course, I wasn’t acquainted with Dai Sil Kim-Gibson prior to meeting her in 1999. But as I learned in subsequent years, her impact on Asian Pacific American cinema might not have been as splashy as other, more self-aggrandizing personalities. It has simply been more profound.

Dai Sil was, arguably, The Last Line of Defense Against Lynne Cheney: in 1978, Dai Sil transitioned from being a university professor of religious studies to serving a stint as a senior program officer in the Media Program of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Cheney, the wife of future Vice President and Republican Party mouthpiece Dick Cheney, served as the Chairperson of the NEH in the years subsequent to Dai Sil’s departure in 1985 and, given the tenor of the Reagan Years, sought to abolish the NEH in 1995 as a perceived target of the Christian Coalition. Dai Sil, by then the director of the New York State Council on the Arts’ Media Program, joined other arts advocates to argue strenuously against the efforts by Cheney and another NEH chair, William J. Bennett to eviscerate the NEH.

As if to drive home the point of her antipathy toward Lynne Cheney, I clearly remember her acceptance speech in 2000 for the Steve Tatsukawa Memorial Fund Award, part of the festivities celebrating Visual Communications’ 30th Anniversary. A couple of years earlier, the efforts to abolish both the NEH and the National Endowment for the Arts ended with an uneasy stalemate and restoration of most the agencies’ pre-Reagan budgets. That didn’t stop Dai Sil from talking about Lynne Cheney. No, sir! From the podium at the then-Japan America Theatre, Dai Sil spent a good portion of her acceptance speech articulating what a danger Cheney was to community-based arts and media, and that if we valued the work that cultural institutions like VC and the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center were doing, we should do everything we can to insure that her husband and George W. Bush were NOT elected President and Vice President that year. As entertaining as her speech was (and as I clearly remember, it generated a lot of knowing laughter from the audience), I think we all knew how the election turned out that year. And though arts funding was largely spared during the Dubya Era, I have to believe it was because Dai Sil and others like her so forcefully advocated for the Arts in those years.

IN AN UNDATED YOUTUBE FRAME GRAB, DIRECTORS DAI SIL KIM-GIBSON AND CHARLES BURNETT ADDRESS THE SOCIAL CLIMATE THAT INCUBATES RACIAL INTOLERANCE. (VIA YOUTUBE)

Dai Sil was also The First One to Cross the Aisle to Meet You: in 1991, she would produce and write AMERICA BECOMING, a documentary feature that examined the new and ever-more diverse generation of immigrants to America and their interactions with more established residents. AMERICA BECOMING would mark the first in an ongoing series of collaborations with Los Angeles-based director Charles Burnett, whose KILLER OF SHEEP (1977) would come to be recognized as a classic of African American cinema. In the pre-L.A. Rebellion years, the idea of a seemingly unassuming African American filmmaking luminary from Los Angeles joining forces with a pushy Korean American neophyte documentarian from New York City was unlikely at best, and inconceivable to most. Three collaborative efforts in, it could be said that Burnett and Kim-Gibson’s creative alliance offers a much-envied template for those who have been too reluctant or pre-occupied to pursue the possibilities of cross-cultural and cross-ethnic creative partnerships.

To this point, I only have to cast an eye on what American society has become in the twenty-three years since Dai Sil teamed with Christine Choy and Elaine Kim — two other strong-willed Korean American women producers — to complete SA-I-GU (1993), a first-out-the-gate examination of the L.A. Rebellion as seen through the eyes of Korean immigrant women. As if to riff off the themes of AMERICA BECOMING, this country’s society has become even more cosmopolitan and polyglot than even seventy years ago, when the confluence of changing immigration policies in the post-WWII years and the civil rights movement served to change America’s homogeneity and political attitudes. Only today, as I cast an eye on the L.A. landscape, I ponder the impact of a multi-ethnic society and the ongoing struggles for cultural plurality and equity. This Film Festival offers a microcosm of those inherent contradictions: as Asian Pacific Americans, we celebrate the broad spectrum of our AAPI-ness at cultural gatherings as diverse as various Asian-centric film festivals, receptions, networking soirees, and empowerment events; we revel in our communities’ culinary offerings through This Night Market and That Plate-by-Plate; hype our Asian-centric food trucks, and champion our AAPI-owned pop-up eateries and barrio barbecue hangouts; and we clamor for full participation and recognition in American society through the realms of politics and mainstream entertainment — vocations that, in a bygone era, would have made our parents keel over in horror and abject disappointment.

I don’t know what Dai Sil Kim-Gibson thinks of all the changes in Asian Pacific America during the three decades of her creative career. As her latest cinematic effort PEOPLE ARE THE SKY points out, in the years since she lost her husband, fellow arts advocate and administrator Don Gibson to a prolonged illness, Dai Sil has turned to painting to keep up her creative chops even as she has been slowly easing back into the director’s chair. I wonder, though, if she’s had a chance to observe this new energy that has emerged in the last decade or so — a new and aggressive push into the mainstream entertainment arena as seen by the likes of directors Justin Lin and John Chu; the rise of AAPI internet celebrities as Wong Fu Productions, Kev Jumba, or even The Fung Brothers; entertainment empowerment initiatives as Kollaboration or the International Secret Agents; or even game-changing broadcast programming as that current flavor-of-the-month, FRESH OFF THE BOAT. Is she heartened by it all? Or is there some unexpressed sense of dissatisfaction in how all these new developments are happening within some kind of “silo,” sealed off from the rest of society and from the challenges and possibilities of cross-cultural collaboration and partnership? I suspect Dai Sil might very well take the long view on this question. That is, we’ve come a long way since she emerged onto the media arts arena. But we all — old-timers and young-bloods alike — still have so very, very far to go.

ABRAHAM FERRER is the Exhibitions Director at Visual Communications and has been involved with organizing the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival since 1988.

For a complete line-up of our Artist's Spotlight on Dai Sil Kim-Gibson, please click here.