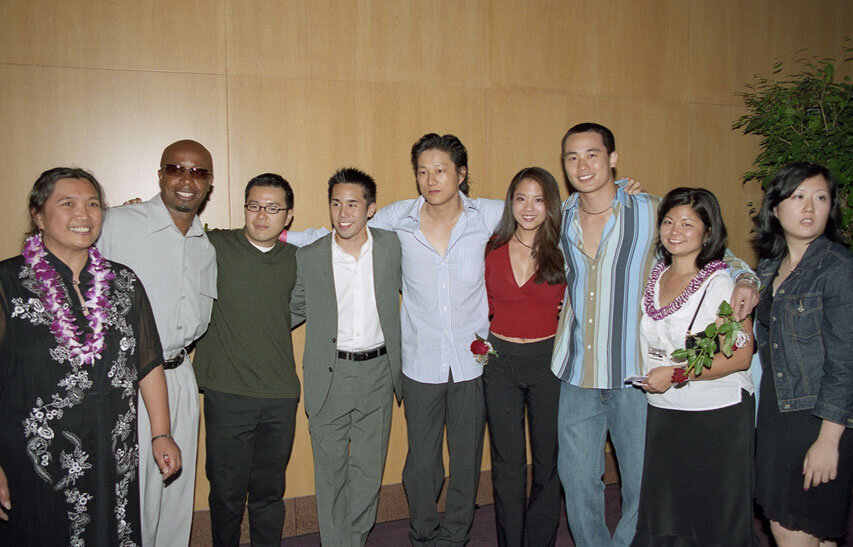

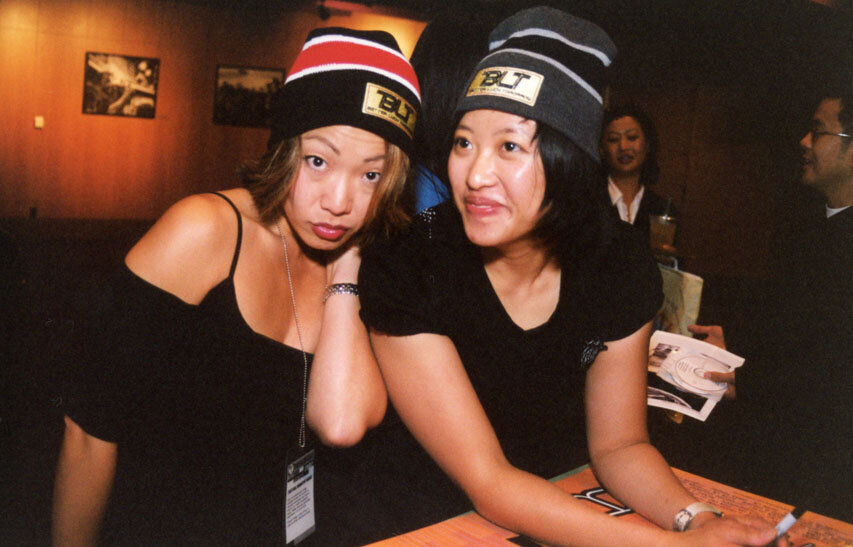

A Festival in Flux: VC and its Film Festival 1999 - 2003

/By Abraham Ferrer

The years 1998 through 2003 were transformative and game-changing years for Visual Communications. Having dissolved its partnership to run the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival with the UCLA Film & Television Archive the year before, VC realized a decade-long dream to settle into a permanent home in the former Old Union Church on the north end of Little Tokyo’s historic district in March 1998. A new home, a new profile for one of VC’s signature programs, and the promise of new program initiatives on the way — the future looked bright for the nation’s premier Asian Pacific American media arts organization.

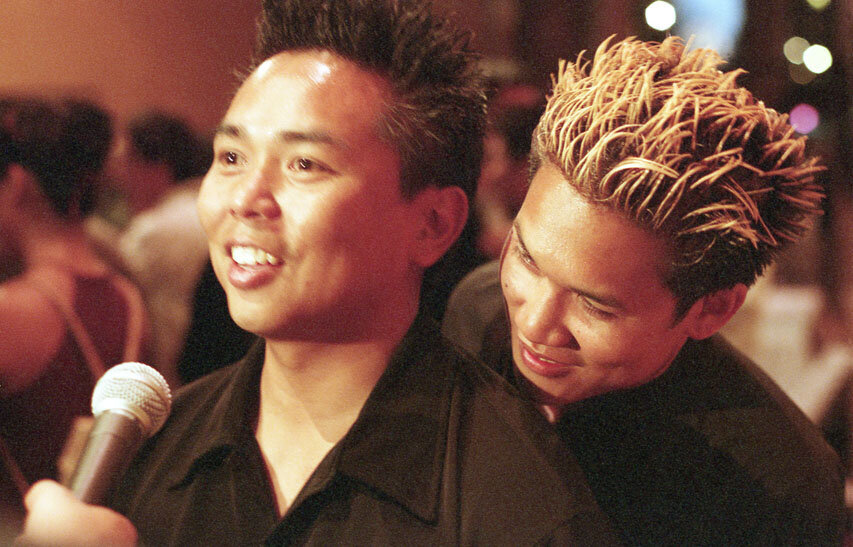

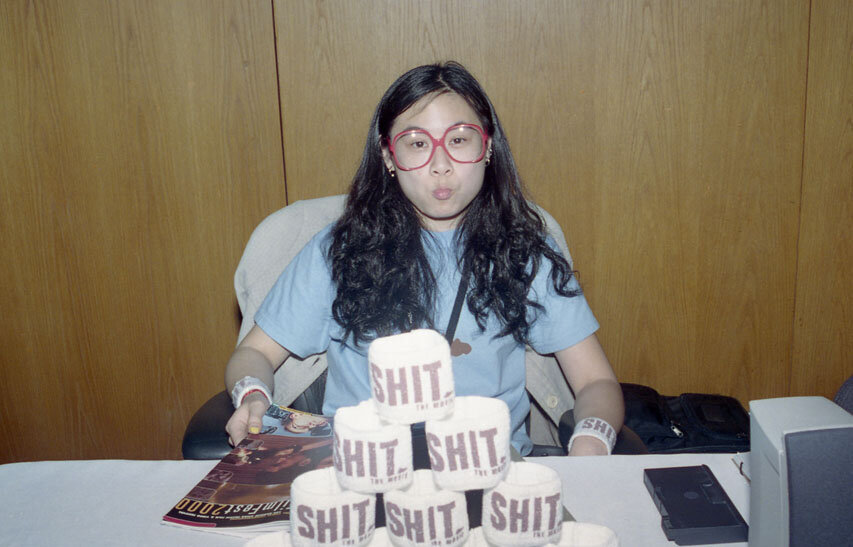

However, one key component of Visual Communications did not survive the transition to a permanent site — VC’s on-site black & white photographic darkroom, a vital workroom that has been a prime feature of VC offices of the past. Anticipating a “filmless” photography future for VC, then-Executive Director Linda Mabalot made the decision to retire the darkroom, and demurred from building such a space in the new space, dubbed the Union Center for the Arts. Thus, a gradual shift began over the course of five crucial years from VC’s arrival in its new space. As the organization’s cultivation of both legacy and emerging artists and audiences was punctuated by the growth of the Film Festival, VC’s still photography policy practically ceased starting in 1998, as film was sent out for color processing and the attendant quality control practiced by VC staffers Robert Nakamura, Alan Ohashi, Keith Lee, and others gave way to an immediacy that pre-dated the arrival of digital photography to VC in 2002.

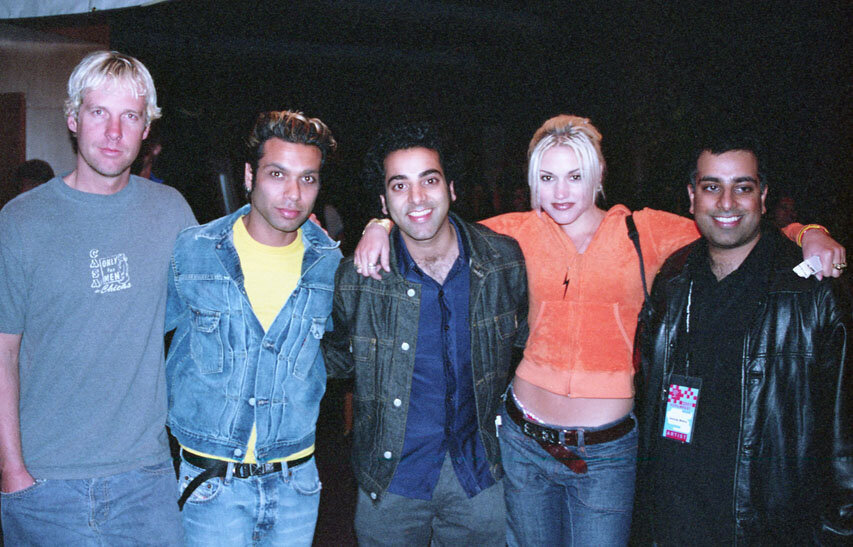

The pictures selected for this online exhibition by Olivia YiSu Stark, Yoon Seok (Raymond) Son, and Kyla Worrell — 2020 Winter Quarter Program Associates from UCLA’s Asian American Studies 185 Capstone class — owe much to the growing sense of fandom that has become a staple of the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival. As well, the back-stories attached to those who were captured by a new generation of VC staffers including Jeff Liu, John Lee, VC associates such as Shane Sato, and others speak to a time when “digital” was not yet in VC’s creative toolbox. A fundamentally altered still photography practice at VC paralleled the organization’s own shift from a creation-based organization to a talent incubator and enabler. Nonetheless, it really was, as is still the case, all about the pictures, and how VC’s photographers saw their subject matter and captured them for posterity.